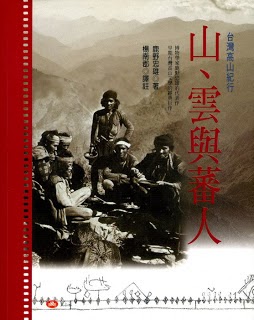

This semester at the University of Ottawa, I am teaching a course ANT4105 Anthropology of Taiwan. We began the class with a documentary film about Tadao Kano.

A precursor to the anthropology of Taiwan, he attended high school in Taiwan, where he began his studies of Taiwanese insects as a high school student. He frequently skipped classes, as he was drawn to the high mountains and their indigenous inhabitants, but his free-thinking school principle decided that he learned more on his own than he would have from books, and let him graduate. He eventually got a Ph.D., making important research contributions not only to anthropology, but also to biology, geography, and geology. Kano’s research collections are now on display at the National Museum of Ethnography in Osaka, which is beyond a doubt one of the best anthropological research institutions in the world.

Thinking about Kano’s work reveals a number of things about anthropology, and about Taiwan. First of all, it shows how anthropology as a discipline evolved out of the naturalism of the colonial period. Kano had relatively free access to Taiwan, its mountains, and its indigenous peoples because he was Japanese, and Taiwan was a Japanese colony from 1895 to 1945. He attended elite schools, so the mountain police tolerated his excursions into restricted areas that needed special permits for entry. His language skills and his propensity to adopt native ways made him accepted into indigenous communities where few outsiders had ever been welcomed before.

Kano was certainly no colonial administrator, and even had his differences with the Japanese state at the time. For example, he published his book on the Yami people of Orchid Island in English – during World War II when such an action risked having him suspected of sympathy with the wartime enemy. But he wanted the entire world to know about Taiwan and its indigenous peoples. The Japanese military responded by sending him on a wartime mission to Borneo, where he disappeared at the age of 38. His wife said that he probably took up life with the forest peoples and forgot to return home. So, Kano’s anthropology was enabled by the fact that Taiwan was a part of Japan at the time.

Second, colonialism created a certain way of thinking about the world, including ways of classifying the peoples, plants, and animals of the colonies. This context led Japanese anthropologists and others to think of Taiwan, or Formosa, as an entry into Oceania. Anthropologists at the time studied the indigenous peoples of Taiwan as representatives of the Malayan or Malay-Polynesian world. In a way, this discourse opened up Japan’s southward expansion. It certainly provided some ideological justification, as it showed the Japanese as the modernizers, making local peoples and natural phenomena into objects to be counted, measured, and codified. Japan brought colonial governmentality to Taiwan for the first time in the island’s history. Kano was not “guilty” of colonizing Taiwan, but he was able to follow his intellectual interests, and get funding from Tokyo, because this social context valorized his work.

The disciplinary boundaries were not so rigid in those days, which is why Kano could let his imagination run free, studying people along with clouds, glaciers, rocks, mammals, and insects. He loved Taiwan, its mountains, and its people. The colonial context aside, he points the way towards a living anthropology, an anthropology that affirms life in all its diversity and embracing its affinities with related fields such as biology. Kano remains an inspiration for researchers in the 21st century.

Throughout the semester, students and I will be blogging about our readings and our thoughts on the Anthropology of Taiwan. Stay tuned for more!

No comments:

Post a Comment